Ruth Padel

Aquilegia Nora Barlow

Published in Hortus Gardening Magazine 2011

The funny thing about Aquilegia Nora Barlow is that Nora hated frills. Multi-layered double flowers, and the pink in those plum-red white tipped petals, were not her sort of thing. But experiment was.

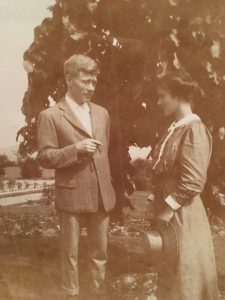

Nora and her husband Alan were my grandparents. They loved William Morris – their house Bowells had several original Morris wallpapers, I remember a lovely flowing design which (I now know) Morris titled Marigolds – but they did not go for floweriness. You didn’t see pink at Boswells unless you brought it with you. Nor lace, scollops, pelmets, tassels or dados.

Like her grandparents Charles and Emma Darwin, Nora disliked the showy. Fabrics she did like, as I remember, tended to be multi-patterned browns, earth colours – a Batik or ethnic look, you might call it now and definitely no cuteness or flounce. I think most of my brothers and sisters and I have inherited that preference – through our mother Hilda, Nora’s surviving daughter. It was a moral as well as an aesthetic stance. Gwen Raverat, Nora’s first cousin, describes Nora in her memoir Period Piece saying obstinately at school, in response to some airy fairy claim by a French teacher, “Ce n’est pas vrai, mademoiselle.”

In gardening terms this meant no double petals, no variegation. Hilda inherited that and so have I. I am currently removing pink and yellow slabs of pre-formed paving out of a backyard in Kentish Town, to make a hedge, trees, lawn, proper beds. As we dream together of what we will plant (once we’ve sorted out the rubble-filled, sour-smelling clay we have sadly uncovered) the gardener helping me keeps coming up against Nora’s aesthetic. “You don’t like variegated,” he says, as if hoping I’ll change.

All the same, I will eventually sew some Nora Barlows, as my mother did in her last garden, in Oxford and will do in her next, in Wiltshire, to see what they will do to other columbines. “As they inter-breed, they make such interestingly different shapes and colours,” my mother says. “They’re so promiscuous! All the features get mixed up, spurs, small petals… You never know what will come up next.”

The appeal is not the look but the unpredictability. It’s a Darwin thing. Hilda remembers Nora doing her columbine experiments in the 1920s when she was ten: at The Warren, Alan and Nora’s first house. Unfortunately Nora had also shown Hilda how to such the nectar out of a columbine’s backward-pointing spurs. (I too remember Nora pointing out to us individual quirks of plants and animals.) One afternoon Hilda went around doing this to all Nora’s columbines and was roundly told off. “But the important ones had caps on, for germination,” Hilda told me recently. “I don’t think I sucked any of those.” It must be pure coincidence, then, that Aquilegia Nora Barlow has no such backward spurs.

I’m amazed now that Nora had the time to experiment on columbines at all. She had six children and ran a large house and garden. In 1930 they moved from The Warren (a house and garden Nora dearly loved, and which they were all sad to leave) to Boswells, built in 1901 by Alan’s father Sir Thomas Barlow outside Wendover, in Buckinghamshire.

The garden was more formal. Sir Thomas had laid it out, Alan helped his father plant the orchard before he married Nora. So Boswells garden was wished on her, she often disagreed with Alan and her preference was for the more wild and rambly. She also had to learn to garden on chalk.

There were two farms attached to the house by a gravel drive. The upper farm, a little way beyond the drive – past the meadow of scabious, tall grass and glorious butterflies – had empty pigsties, calves and cows. It also for a time, to my joy, had a huge roan carthorse on whose warm back I once sat. There was a red-brick, high-walled kitchen garden there too, where I remember picking red gooseberries at Nora’s command.

The lower farm, at the end of a rutted lane, was called Well Head Farm: that was for machinery and hay and I hardly remember it. There were a lot of staff, at both farms and in the house, to consider; people came and went as Boswells alls the time. Nora was very active in the local Botanical Society – there were many wild orchids nearby – and friends came to stay all the time. But through all this Nora was also working on and editing Darwin’s manuscripts.

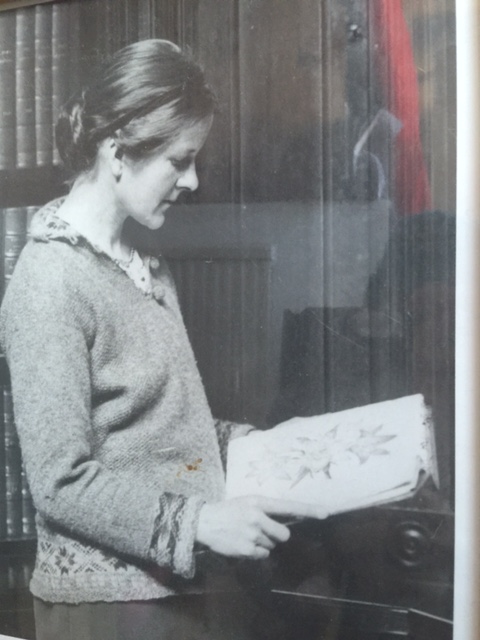

Her edition of Darwin’s Diary of the Voyage of H.M.S. Beagle came out in 1945. The years I remember come later, of course, her years of grandchildren when I, my brothers and sister, and our many cousins were being welcomed at Boswells. I remember large grown-up dinner parties to which I occasionally came down in my nightie and was banished upstairs; Christmas staff parties for people from the farm, visits from local botanists. But in those she must have been working on her edition, the first unexpurgated edition, of Darwin’s Autobiography. This appeared in 1958. Then she worked on a book which must have taken endless research as well as thought, the letters between Darwin and John Stevens Henslow, Professor of Botany at Cambridge,who was responsible for the invitation the young twenty-two year-old fresh from a Divinity degree suddenly received, to accompany the Beagle’s voyage as geologist.

Henslow had proposed Darwin to the Admiralty. During the five years of the voyage Darwin often wrote to him about zoological and botanical specimens he was sending back to Cambridge. Under Henslow’s guidance he increasingly came to rely on his own judgement. It was like a long-distance relationship with the supervisor of your PhD and all Darwin’s subsequent work rested on it. By the time he was back in Britain, his ideas had outstripped Henslow’s and you can see him in the later letters limiting what he says, not to offend his old mentor. But the correspondence shows how important Henslow was to him in the early years and Nora subtitled this book The growth of an idea.

This came out in 1969, when I was doing Finals. Alan died and she moved to Cambridge, where she had grown up, to a house called Sellenger, which had a large mulberry tree and a vigorous passion flower. It is now a graduate house for Robinson College. Nora’s dining room and drawing room are graduate rooms and a new dormitory has been built in the long rambly orchard. Nora would have approved: Alan was on a commission to se up new universities after the war, Robinson is a new college and Nora like Alan was a firm believer in expanding higher education.

In the 1970s, when Nora’s short-term memory had become creatively shaky, I spent a couple of weeks with her at Sellenger, cooking and companioning while her housekeeper was on holiday. She would ask after my own PhD, which was on Greek tragedy’s understanding of emotion, and then ask again, forgetting she had asked before. Each time she provided a different association to Darwin’s Expression of the Emotions in Man and Animals, which, shamefully, I had not then read.

At Boswells, despite the huge beautiful garden which needed so much work, and the scholarship, and all the human commitments, she always seemed to have time for you. She would sit at her desk, by the window of the drawing-room where a Garrya Elliptica dangled catkins outside the leaded panes, and if a child came in she would put another layer of fabric over the papers (her desk became an archaeological sandwich of letters, papers and textiles) and get up to show you things in the garden – and enjoy you discovering them.

I never, of course, saw The Warren. Hilda says it was a big lovely garden, wilder than the more formal Boswells. I was always aware there had been another, even more special place, as you are dimly conscious of a Golden Age before your own, but to me Boswells was paradise: I think to my brothers and sister and probably my cousins, too.

Nora’s mother Ida had run a lovely Cambridge garden on the Huntingdon Road where New Hall now stands. (Nora and her sister Ruth gave it to the university for a woman’s college. For my mother Hilda, that was the magical place: Ida used to bring back plants for it from abroad. But both Nora and her cousin Margaret Keynes (Gwen Raverat’s sister, another Darwin grand-daughter) conjured up in their own establishments something of the atmosphere of their grandfather’s house – Down House, Darwin’s home in Kent.

Raverat says that for her aunts and uncles, Darwin’s children, Downe was a sacred place, and I felt something similar for Boswells. The first time I went to Downe I felt the air of something familiar from afar. For me the essence of that atmosphere, at Boswells as at Downe, was the close relation between house and garden, and the naturalness with which children could run from one to the other.

At Boswells, the liminal place was the verandah running across the centre of the back of the house. Along the width of this stood a seven foot oak table, usually covered with stripy cloth and untidy bric à brac. From here you looked out between rendered grey pillars at the garden, In front of you was a path running left to right like the front of a stage, its straight edge before the large lawn softened by an egg-shaped patch of Jerusalem sage, Phormium lusitanica, like a pale-green pool about three feet wide. I used to love the challenge of jumping over it. Over the sage, you looked out to the end of the long herbaceous border whose two beds were backed by hedges and a secret little grassy path running behind the right hand one. It must have been hell, I now realize, to mow.

At the end, backed by tall trees backed by distant woods, a little path led off right into a wood. You could get into that wood also close to the house, over a bank that led off right from the lawn. A path bent up through that wood, through hazels, past the row of Alan’s velvety compost heaps – where the little green-handled fruit knives often turned up in the scrapings from the dining-table – towards the blue-green gate which led into the woods and hills behind.

If you let your eye travel left from the verandah, you saw the weeping elm, the House Tree whose skirts reached to the ground, and beyond it the double yew hedge (scary and dark, it had to be run along, not walked through), and beyond that the tinker’s caravan where I spent hours playing.

I thought of this as a gypsy caravan but to my mother it was just a little hut on wheels for shepherds to sleep in during lambing. I begged to be allowed to sleep in it one summer, with the cook’s daughter, Irena, and Nora was all for it but my father wouldn’t allow it.

The caravan was set in a meadow with a great climbable cedar. To the left again was the back of the summerhouse, if you ran past a great bush buzzing scarily with insects you got to the summerhouse front, piled with long- discarded wicker chairs which looked onto the croquet lawn. Go down the crocquet lawn, backed to the left by a yew hedge and to a right by the view of open fields, and then down a little bank and you were in the scabious meadow again.

This ran along one side of the front drive which led down to the farm. But you could cross that drive – looking back left at the house and the pillars before it – and pass prickly round cushions of gorse and sweet-smelling Old Man you could crumble in your fingers, and go into a quite different, more secret and enclosed garden,. There was an old tennis court there, which I wasn’t interested in, and the first sundial I had ever seen.

Recently, finishing a book of poems and prose on migration (The Mara Crossing, which will come out January 2012) I found myself writing rather obliquely about that sundial, and the migration of Painted Ladies from North Africa, by a sudden memory of standing there with Nora.

Perhaps it’s also an even more oblique elegy for her, too. It remembers her quietly pointing something out, revealing nature to a child just as Darwin’s children remembered him doing for them, at Downe.

Ethogram for a Painted Lady

I’m six and we are keeping still.

We’re looking at shadow on grey stone

in the sunken garden

and an orange-black fan – two fans, really,

with dribbles of milk on each tip

and a bravura range of little eyespots –

looking back at us. I have never heard

of Morocco, or anything outside this strip

of Eden with its secret sundial

I thought only I knew,

but I will remember standing here

with my Grandmother, watching

flying blossom of the meadow

sun itself. Maybe I’m there still,

I never left and I’ve never heard

of Morocco where these guys

stream in from, steering

by polarized light into Europe

over the Straits of Gibraltar,

funnelling in on the shortest sea crossing

like eagles gliding from thermal to thermal

on the same route:

a million-thick cloud of half-inch souls

swarming to the fields of asphodel.

Ruth Padel, Hania, Crete, October 2011, with many thanks to my brother Felix, and to Hilda, for long-distance research.